I like to think of myself as a part-time private investigator. I spend hours researching and digging in to people’s lives. It just so happens that the people I investigate are dead. But being an armchair investigator is fun even if it isn’t as cool as Sam Spade or Magnum P.I.’s mustache.

Recently I became obsessed with trying to find Elizabeth Floyd’s father. Elizabeth is my 5x great grandmother and was married to George Foulk. She was born 13 Sep 1781, likely in Monongalia, WV and died 16 Mar 1868 in Mercer, PA. Much of this information was taken from Millie Covey Fry’s great compendium website on the Foulk/Volck family. There is no information on who her father or mother were. In some family trees on ancestry.com, I saw lots of talk about a William Floyd being her father and having been born in England died during the Revolutionary War. There were many that listed her mother as being named Cynthia, but with no other information. I could never prove that William Floyd was Elizabeth’s mother. No documentation at all.

But as I kept rereading Millie Covey Fry’s website, I saw all the excerpts about the Floyd family and their legal transactions with the Foulks in Monongalia, WV (then part of VA.) Pieces started to fall in to place.

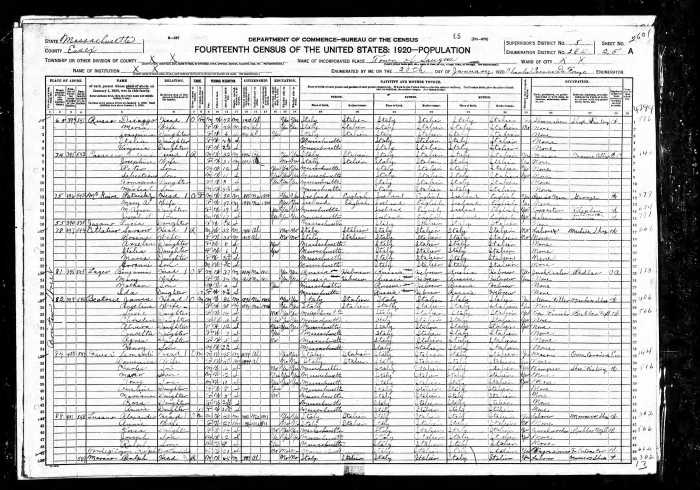

George Foulk was born 1774 in Frederick County, VA to Jacob and Margaret Foulk. Before the turn of the 19th C., George is living in Monongalia, along with the rest of the Foulk clan, especially his father Jacob.

on 6 Jan 1798, James and Mary Matheny sold land on Cheat River to Henry Floyd. Jacob Foulk was witness

On 9 Mar 1804, John Floyd (of Fayette Co. PA) was sold 11 1/2 acres on Pharoah’s Run by Christopher and Mary Erwin. This as part of 90 acre tract of land sold by Charles Snodgrass to Jacob Foulk.

In Sep 1807, Jacob Foulk and his wife Margaret, sold 78 acres (adjoining Charles and William Snodgrass) to Thomas Floyd.

7 Oct 1809, Thomas and Drusillah Floyd sold 32 1/2 acres on Phraroah’s Run to John Snodgrass. Part of tract conveyed to Floyd by Jacob Foulk.

29 Dec 1817, George and Elizabeth Foulk (of Trumbull, OH) sell Michael Floyd 114 1/2 acres (for $400) in Monongalia County, VA on Pharaoh’s Run. “It being a part of two tracts conveyed to John Floyd and from him to the above named Elizabeth Foulk,”

And, in reiteration of the above information, another book quotes the transaction as such, “1817- 114+ acres in two tracts from George Foulk and Elizabeth his wife to Michael Floyd, acknowledged by George with Elizabeth’s dower release.”

With this information, I contacted a friend of mine who is a lawyer and told him that based on this information, would I be correct in assuming that the this Elizabeth’s first and only marriage was to George Foulk, then it was most likely that her father provided her land as part of her dowry? He said that it was likely, and that the other possibility was that she was a widow and received the land from her deceased husband. However, I know that Elizabeth was only married once and it was to George Foulk.

So in December 1817, when George Foulk and his wife Elizabeth (Floyd) sell land to Michael Floyd, they are selling land that John Floyd had given to Elizabeth. Therefore, my assumption would have some legal basis that John Floyd was Elizabeth’s father. This is confirmed when it is stated in the Monongalia County, (West) Virginia, Records of the District, Superior and County Courts that the sale was “acknowledged by George with Elizabeth’s dower release.”

The significance of a dowry and the dower release is that a dowry was provided by the bride’s family, usually the father as he was likely the landowner, at the time of marriage. The dowry meant that the husband could not sell the entire share of the property without consent of his wife. The wife was legally able to keep at least 1/3 of the property so she would never be destitute. However, the wife was able to release her dower and allow the husband to sell the property, as Elizabeth allowed George to do. I am in no way, shape or form, a lawyer, but this is how I read the information during my research and it makes sense. In basic terms, if the husband died, the wife was able to keep a portion of the land to live on or sell for money to subsist.

Through all of this, I also came to the conclusion that Michael Floyd and Henry Floyd mentioned above, were her uncles and John’s brothers.

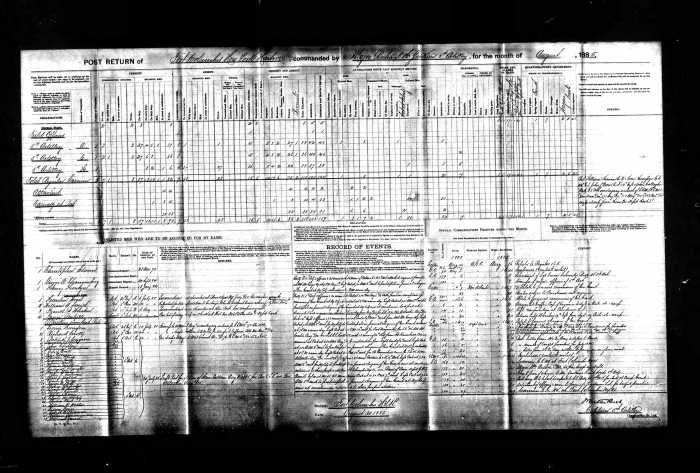

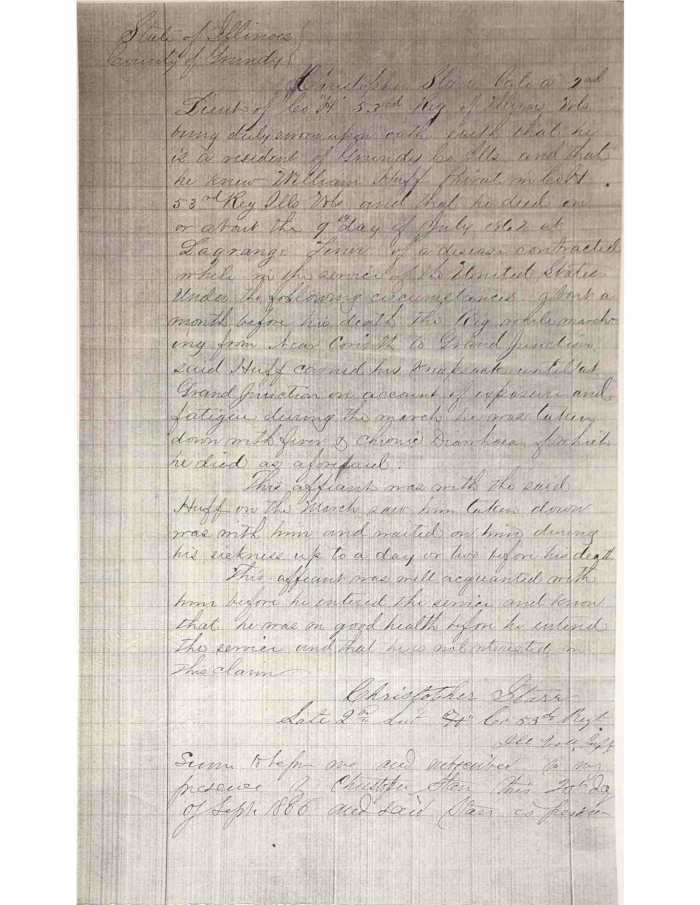

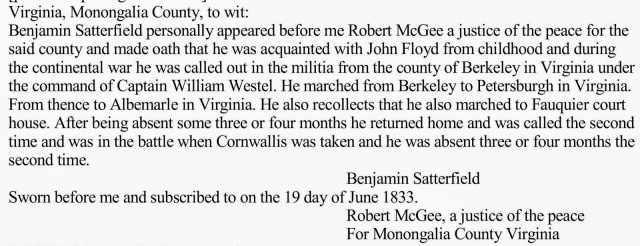

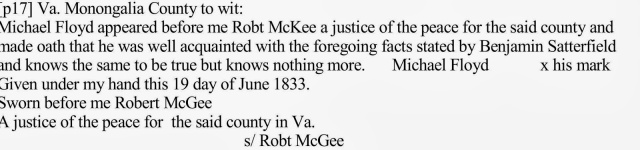

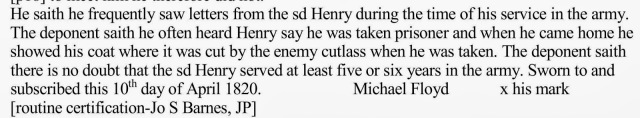

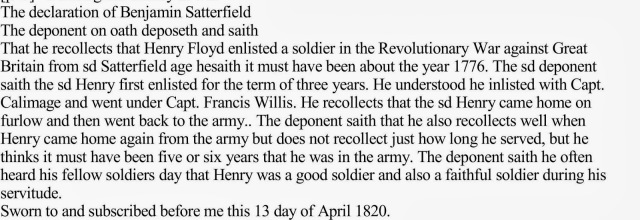

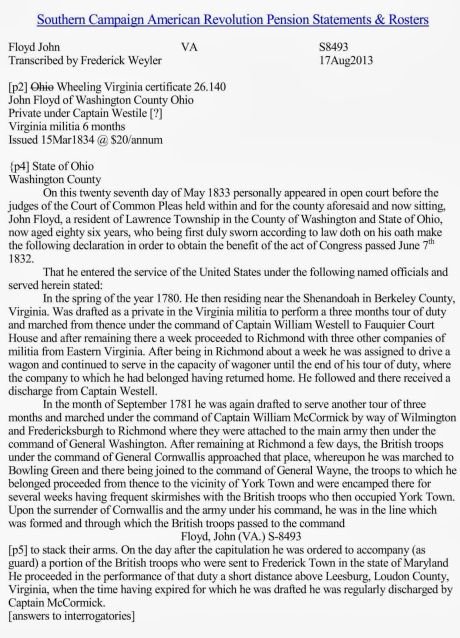

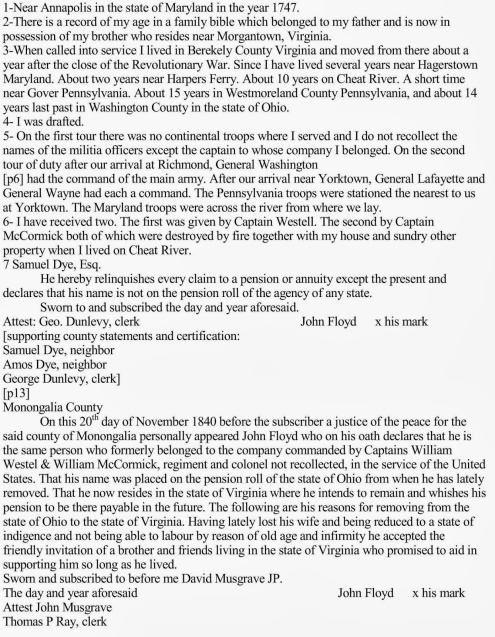

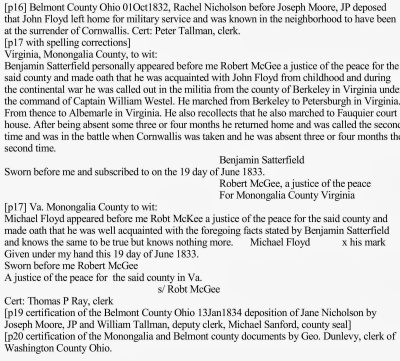

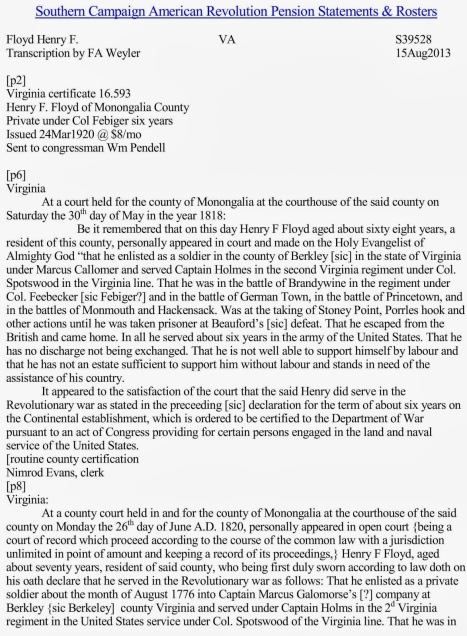

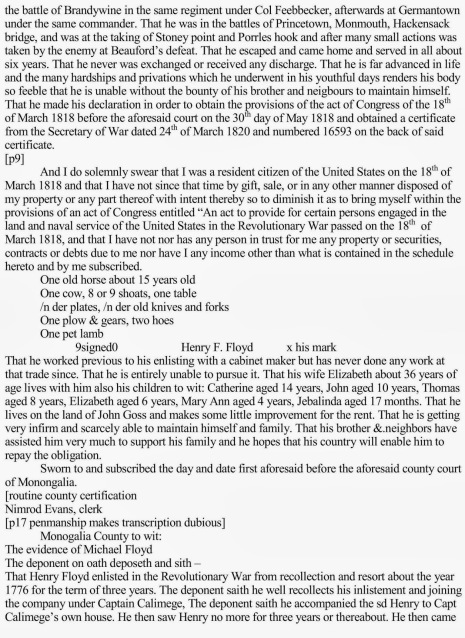

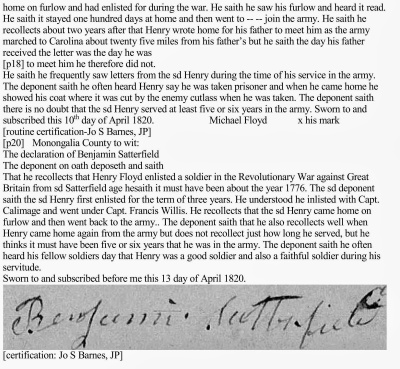

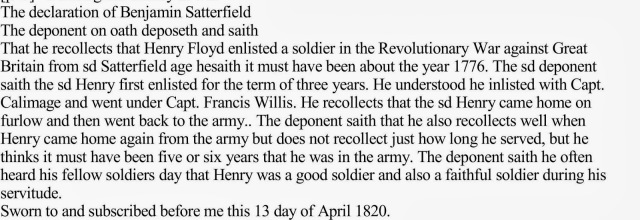

I was able to confirm this as much as any amateur genealogist can (nothing is 100%) when I found John Floyd’s and Henry Floyd’s Revolutionary War Pension Claims. In these documents from the 1820 (Henry) and 1833 (John,) we see that Michael Floyd testified on their behalf, as did their childhood friend Benjamin Satterfield.

Of course Michael could be a cousin, but in John’s pension claim in 1833, it states that he moved back to Monongalia to live with a brother, who I would presume to be Michael because Henry had passed away in 1829.

I still have no idea who Elizabeth Floyd’s mother is, but at least I’m making progress. I will find out.

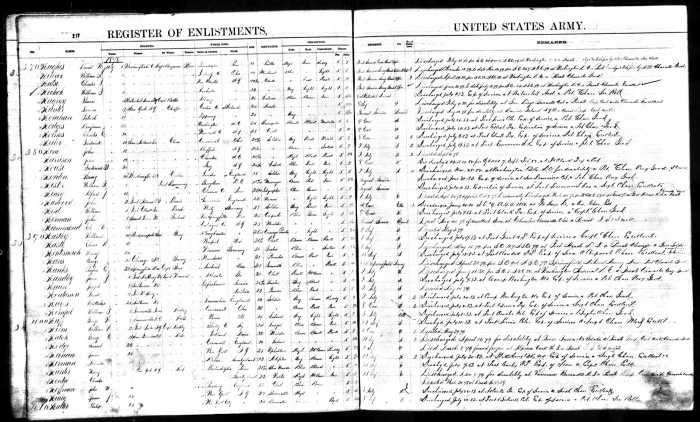

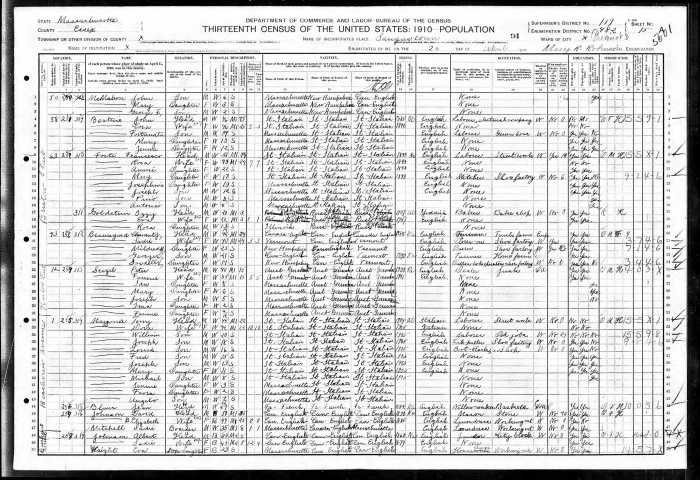

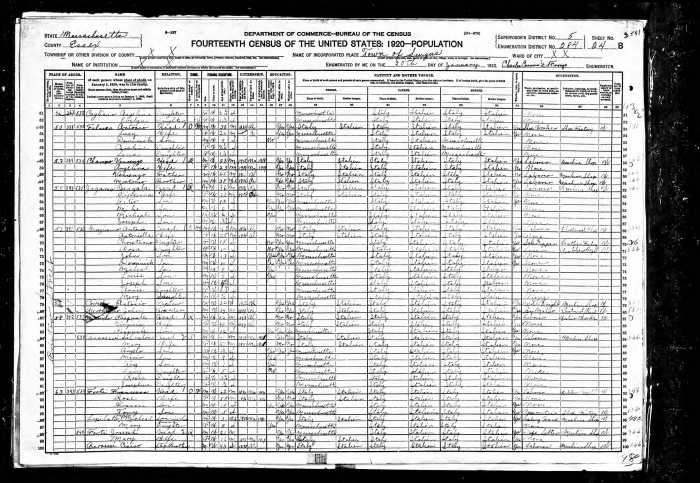

Below are the full American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters for John and Henry Floyd: